Combining transdisciplinary challenge-based education with design thinking creates a unique environment for students to learn skills that will help them navigate sustainability transitions, according to a paper in the Journal of Chemical Education.

The twenty-first century so far seems to have been a century of striving for transitions, as seen in the energy transition, the protein transition and, more recently, the transition to sustainable chemistry. According to Fieke Sluijs, Sabine Uijl, Eelco Vogt and Bert Weckhuysen from Utrecht University (UU), the current way of training chemists is not sufficient to address the sustainability issues that have arisen in recent decades. They found that a good way to prepare students for these challenges is through transdisciplinary, challenge-based education combined with design thinking, and they are exploring this education system in the Da Vinci Project, functioning as an extracurricular programme for bachelor students.

‘We need graduates who can drive and accelerate the transition to sustainable and circular chemistry’

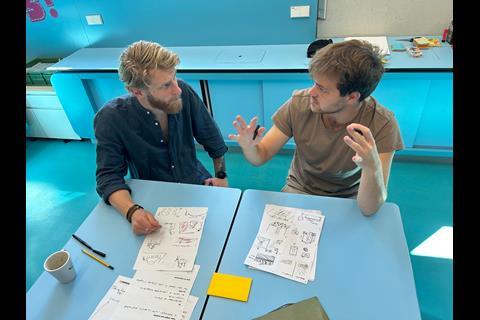

In contrast to traditional scientific skills, this type of education is much more focused on personal and professional capabilities. Using real sustainability challenges posed by companies and organisations, bachelor students go through a cycle of empathising (immersion in the world of the end user), defining the problem, generating ideas, making these ideas tangible through prototyping, and testing the ideas and prototypes.

Change-makers for sustainability

The aim of the Da Vinci Project is to give students ‘competencies for sustainable development’, which ‘cannot be taught, but must be developed by the learners themselves through action, experience and reflection’, according to the researchers. These include systems thinking, implementation, integrative problem solving, and inter- and intra-personal competencies, such as empathy, creativity, collaborative teamwork, and stakeholder engagement, all of which need to be integrated for a student to become a ‘sustainability change-maker.’

‘Some of the students stated that the project really changed their way of looking at things’

Fieke Sluijs, first author of the paper and researcher at UU, shares that she was surprised by the students’ feedback. ‘Some of them stated that the project really changed their way of looking at things. One student said that she felt more courageous to take risks when applying for a job that she wouldn’t have applied for without the Da Vinci Project.’ Another student told Sluijs that he used more creativity in his school assignments and didn’t just follow instructions, which was highly appreciated by his professors and increased the quality of his work. Although this is based on feedback from only the first year, ‘the bottom line is that their responses indicate that the Da Vinci Project has had a longer lasting effect than I expected’, says Sluijs.

Priorities

This type of education system is quite time-consuming and has a high workload for both students and staff, but the paper stresses that this is a necessary form of education if we want to educate students to be sustainable “change-makers”. Sluijs argues that it is a question of priorities. ‘When you have limited resources, you must spend them wisely. I think it is important to find a way to make transdisciplinary, challenge-based education accessible to students, because in the long run we need graduates who can drive and accelerate the transition to sustainable and circular chemistry.’

‘It is important to find a way to make transdisciplinary, challenge-based education accessible to students’

When comparing the costs of running the bachelor’s and master’s programmes, they don’t exceed those of the living lab programmes offered by universities of applied sciences, Sluijs continues. ‘However, a lot of time, money, energy and other resources are now spent on the organisation because the organisational and financial structures of our universities do not facilitate this type of education.’ But she foresees a change. ‘I think that in the future these structures will become more flexible, and we will be able to reduce the costs of organisation because it is in the policy of many universities to facilitate more transdisciplinary learning. I also believe that over time this type of education will become more and more advanced and will add more value, not only for the students, but also for science and society. Of course there are alternatives, all kinds of “light versions” for example, but the lighter they become, the less impact or value they will have.’

Sluijs, F. et al. (2024) J. Chem. Educ. 101(10), DOI: 10.1021/acs.jchemed.4c00158

The Da Vinci Master Programme

The Da Vinci Master Programme has a completely different structure compared to the bachelor project. The master programme is a 20-week full-time course for master students, organized in cooperation with Wageningen University & Research and Eindhoven University of Technology. ‘We ran a pilot of the master’s programme last year’, says Sluijs. ‘Working full-time on a complex challenge which involves collaboration with multiple stakeholders has a huge impact on the students’ experience, because it’s very immersive. The relationships within your team, with your supervisors and with people from non-academic partner institutions become very important because your learning process and the results you’re trying to achieve depend largely on them.’ Developing interpersonal and intrapersonal skills becomes even more important.

The challenges in the master’s programme are also more complex and open-ended than in the bachelor’s project, but Sluijs observed that the master’s students are also more mature and professional. ‘You can give them more freedom to take the challenge and run with it. I saw that the students were able to completely turn the challenges around, even initiating new projects

Nog geen opmerkingen