Soft materials for surgical robotics, that’s the goal of a group in Groningen. They have recently made a surprising step in the right direction, as reported in Science.

To use robots in surgery, you have to make them small. Up to a scale of a few millimetres, traditional mechanical and electronic components are a good choice. But if you want to go even smaller, the rigid components become an obstacle. ‘An alternative that comes from the biomedical field is found in soft materials’, says Michael Lerch, assistant professor of Autonomous Soft Materials at the University of Groningen. ‘Think of a material like contact lenses: they are biocompatible, do not damage tissue and are easy to manufacture. But one big disadvantage is that programming their movements is bloody difficult.’

Traditionally, soft materials can only contract and expand in all directions at the same time, more or less like a sponge. For certain classes of materials – liquid-crystalline elastomers (LCEs) – directional motion is possible, but remains simple. ‘Ultimately, however, we want to perform more complex movements, such as the motions for drinking’, says Lerch. ‘Our main question was: how can we build such movements from simple building blocks, even within the same material?’

Puzzled

Lerch and his group found a lot of potential in LCEs, which are polymerised liquid crystals, the rod-like molecules found in LCD screens. ‘If you stimulate them with heat, for example, they can switch from an ordered to a disordered state, which is called a phase transition’, Lerch explains. ‘Fun fact: the first Dutch female PhD in chemistry, Ada Prins, was working on liquid crystals in Amsterdam at the beginning of the twentieth century.’

Liquid crystals have many different phases, which means that the molecules can be packed in many different ways. Depending on the molecular structure and the conditions, you can hop between these phases, says Lerch. ‘The beauty of LCEs is that these polymers can also go through different phases, but in a way that we did not quite expect.’ Together with researchers from Harvard, they discovered a way to make some phase transitions to show different motions. ‘By chance, we found that some transitions give two movements in opposite directions, which is highly unusual.’

‘We were really puzzled when we discovered these two opposite deformations, as it wasn’t our goal’, Lerch continues. This was all the more the case because the general consensus is that the deformation only takes place in one direction. ‘It was a big surprise and really amazing to see.’

Zigzag

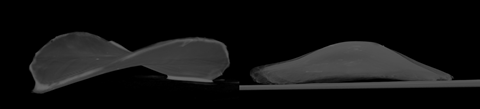

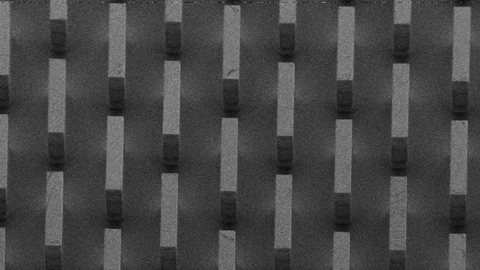

These two movements are seen in the transition between the chevron Smectic C and Smectic A and are described as successive shrinkage or expansion and right-handed or left-handed twisting and tilting in opposite directions. Lerch: ‘Smectic C has a zigzag pattern, while Smectic A is flat. If you stress the materials, you get a folding pattern that resembles folded geological layers.’ The reason for this folding was also a surprise. ‘When the molecules start to polymerise, stress from polymerization will have a directional effect on the material because the whole thing is already ordered.’

The next big step would be to see if this material could be used in a biological environment. ‘But first we need to lower the temperature used for movement, and we want to be able to trigger the deformations with light and other stimuli as well’, says Lerch.

Gap

Looking at the big picture, these materials could be seen as a kind of middle ground, Lerch philosophises. ‘At the molecular sub-nanoscale, you could work with molecular machines. At the centimetre and millimetre scale, there’s still the possibility of standard electronics, but in between there’s a difficult gap where you have to find new ways of moving and controlling things. That’s why our group is involved in projects with surgeons and roboticists at the UMCG [Universitair Medisch Centrum Groningen, ed.], because we believe that if we push this research further, we will be able to make surgical interventions less invasive.’

Yao, Y. et al. (2024) Science 386(6726), DOI: 10.1126/science.adq6434

Nog geen opmerkingen