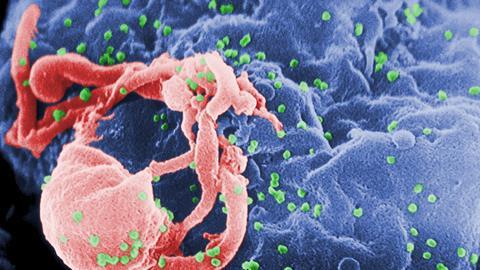

A variant of the HIV-1 subtype-B that is more infectious and virulent than previously known variants has been circulating in the Netherlands for twenty years.

HIV is a virus that, without treatment, leads to AIDS, or acquired immune deficiency syndrome, and causes, among other things, a large decrease in CD4+ T-cells by infecting these and other immune cells. An international research group with institutes from nine countries, including Stichting HIV Monitoring, the University of Amsterdam and the University of Oxford, shows that a new variant has been circulating in the Netherlands for about 20 years.

The researchers discovered the new variant through the BEEHIVE project, a project that connects infected individuals who are relatively certain about when they became infected (6 to 24 months after a positive test). Initially, they found seventeen individuals with the new variant, of which fifteen were from the Netherlands, one from Belgium and one from Switzerland.

To get a better picture, they analysed data from 6,706 participants in the Dutch ATHENA cohort. They found a total of 109 people with the so-called VB variant (after ‘virulent subtype-B’).

The main findings of the studies are that this new HIV-1 subtype B causes a higher virulence and a higher viral load: about 3.5 times as many viral particles per millilitre of blood. Also, the decrease in CD4+ cells was faster when people with the VB variant did not receive treatment.

Fortunately, the new variant is just as treatable as the normal variant and there is no great difference in survival rates with treatment. Furthermore, the researchers reported that 82% of ‘VB-individuals’ were men who had sex with men (compared to 76% in the normal variant).

The mutations of the VB variant seem to have arisen de novo, so not by recombination. The researchers found mutations in 250 amino acids and 509 nucleotides, in addition to insertions and deletions. Because the mutations are spread across the viral genome, it cannot really be determined why this variant is more dangerous than earlier variants. In any case, they conclude that early treatment of HIV – in addition to prevention of transmission – is the best way to prevent the emergence of further and potentially more dangerous HIV variants.

Wymant, C. et al (2022) Science 375(6580), DOI: 10.1126/science.abk1688

HIV is a virus that, without treatment, leads to AIDS, or acquired immune deficiency syndrome, and causes, among other things, a large decrease in CD4+ T-cells by infecting these and other immune cells. An international research group with institutes from nine countries, including Stichting HIV Monitoring, the University of Amsterdam and the University of Oxford, shows that a new variant has been circulating in the Netherlands for about 20 years.

The researchers discovered the new variant through the BEEHIVE project, a project that connects infected individuals who are relatively certain about when they became infected (6 to 24 months after a positive test). Initially, they found seventeen individuals with the new variant, of which fifteen were from the Netherlands, one from Belgium and one from Switzerland.

To get a better picture, they analysed data from 6,706 participants in the Dutch ATHENA cohort. They found a total of 109 people with the so-called VB variant (after ‘virulent subtype-B’).

The main findings of the studies are that this new HIV-1 subtype B causes a higher virulence and a higher viral load: about 3.5 times as many viral particles per millilitre of blood. Also, the decrease in CD4+ cells was faster when people with the VB variant did not receive treatment.

Fortunately, the new variant is just as treatable as the normal variant and there is no great difference in survival rates with treatment. Furthermore, the researchers reported that 82% of ‘VB-individuals’ were men who had sex with men (compared to 76% in the normal variant).

The mutations of the VB variant seem to have arisen de novo, so not by recombination. The researchers found mutations in 250 amino acids and 509 nucleotides, in addition to insertions and deletions. Because the mutations are spread across the viral genome, it cannot really be determined why this variant is more dangerous than earlier variants. In any case, they conclude that early treatment of HIV - in addition to prevention of transmission - is the best way to prevent the emergence of further and potentially more dangerous HIV variants.

Wymant, C. et al (2022) Science 375(6580), DOI: 10.1126/science.abk1688