Regenerative medicine aims to deploy our body’s capacity for regeneration as a means to repair or replace diseased tissues and organs. A striking discovery in armadillos, which surprisingly involves the bacterium that causes leprosy, offers a new perspective on how the liver can (re)grow in a healthy manner.

Replacing diseased, damaged or aged tissue by deploying the body’s own regenerative power to create new and healthy tissues. That is the starting point of regenerative medicine, which is all about harnessing our body’s capacity for self-repair and renewal. Various strategies are under development, such as administering stem cells or by implanting lab-grown tissues. Another approach is to use advanced biomaterials that provide the right environment for cells to grow and differentiate. Those materials act as a mould or scaffold into which new tissue can grow. To do so, these materials must secrete the right chemical signals that trigger the desired cell and tissue growth.

But what are the right signals and, most importantly, how do you ensure that those signals produce a functional organ and do not lead to unstructured tissue growth or even tumour formation? A recent discovery offers inspiration from an unexpected source; the leprosy bacterium. In Cell Reports Medicine, Anura Rambukkana’s group (University of Edinburgh) recently published the results of their study on liver increase in armadillos infected with Mycobacterium leprae, the cause of the severy disfiguring disease leprosy in humans. Armadillos are a natural host of M. leprae.

Highjacking cells

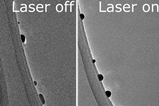

M. leprae has developed a special strategy to thrive in armadillos. The bacterium ‘highjacks’ Schwann cells - nerve cells involved in regeneration - in the liver and initiates their partial reprogramming, which in turn triggers growth processes in the liver, making more tissue available for the growing bacterial population. The striking thing, however, is that this growth of the liver occurs in a healthy, normal manner including functional architecture and vasculature of the tissue, but without fibrosis or the formation of tumours. The result is a ‘normal’, only larger armadillo liver.

This offers a whole new perspective on how the growth of healthy, adult tissue can take place in the body. Partial reprogramming of the right type of cells can apparently induce functional regeneration. In armadillo, this reprogramming involves increased expression of genes that ensure, among other things, the construction of blood vessels and bile ducts, the production of collagen and the expansion of the extracellular matrix that shapes and supports the new tissue. Many of these genes also have human equivalents.

According to the researchers, this model offers new opportunities to study liver tissue regeneration. Perhaps it also provides leads for therapeutic applications. Although the liver has the greatest regenerative capacity of all our organs, it is still very challenging to induce regeneration of diseased and damaged livers (chronic liver inflammation is a major indication) in a healthy way.

Nog geen opmerkingen