Single-cell techniques offer many possibilities, but it is difficult to reach all the cells inside organs. Researchers at MIT have developed a new approach that brings those hard-to-reach parts into brilliant focus.

The development of single-cell technologies has provided many new insights into the heterogeneity of cells within tissues and organs. The ability to sort, count, sequence and visualise individual cells is enabling entirely new quantitative analyses of complex biological processes, cell populations and the spatial context in which many processes take place.

However, these techniques require multiple steps in which cells are fixed, labelled and washed. To obtain reliable, quantitatively relevant measurements, it is essential that all cells are pre-processed and treated in the same way. This works well for single cells (1D) or very thin slices of tissue (2D), but the ability to analyse whole, intact organs or tissues at the single cell level is limited. Now, researchers at MIT’s Picower Institute are changing that with a new 3D approach that allows them to label all the cells in entire organs.

One of the difficulties in treating organs is that the antibodies used for labelling have difficulty penetrating the cells in the inner, compact regions. Research leader Kwanghun Chung likens it to marinating meat. ‘If you put a piece of meat in a marinade, the outer layers will quickly absorb the marinade, but nothing inside will change. The same is true for cells in a tightly packed tissue, but it will interfere with your measurement. Longer marination helps, but this makes labelling whole organs a very time-consuming process.’

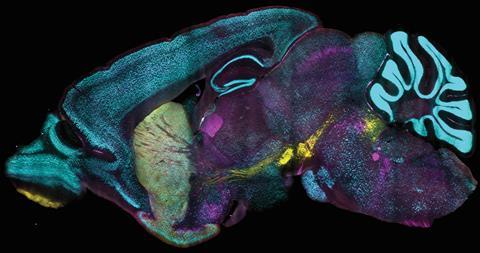

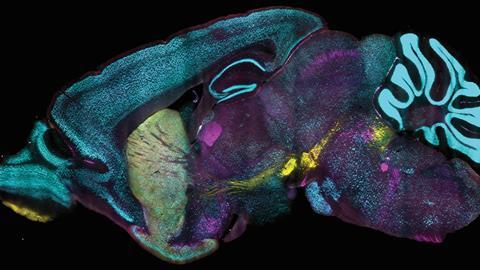

In addition, the chemicals you can use to reach the inner layers of tissues are so aggressive that you disrupt the integrity of the cells, which also prevents you from getting a good measurement of an intact organ. Building on previous techniques from the Chung lab, such as CLARITY, SHIELD and SWITCH, the team has now developed CuRVE, which allows them to perform – as shown here – 3D single-cell imaging on an intact mouse brain.

The trick is to play with what is known as the speed mismatch: the discrepancy between the slow speed at which antibodies move through tissue and the speed at which they bind to their target and therefore stick mainly to cells in the outer layer. By switching the binding capacity of the antibodies on and off in a controlled manner using deoxycholic acid (which, after extensive screening, was found to be effective but not destructive), varying the pH of the ‘bath’ and applying an electrical voltage, the researchers managed to get the antibodies to penetrate deep into the interior to bind to the desired targets. The result was a stunning single-cell view of the mouse brain.

Dae Hee Yun, Young-Gyun Park, et al., Uniform volumetric single-cell processing for organ-scale molecular phenotyping, Nature Biotechnology (2025), doi:10.1038/s41587-024-02533-4

Nog geen opmerkingen