How far does sign language go in chemistry? C2W | Mens & Molecule spoke to four deaf scientists to find out about their most common struggles, how signs for scientific concepts are created, and the (unexpected) benefits of sign language in chemistry.

1880 was a dark year for deaf people in Europe and the USA. In that year, an international conference was organised in Milan by a group who were opposed to sign language and wanted deaf children to learn to speak and lip-read ‘normally’. By cleverly choosing the participants, it was decided that sign language would be banned in schools that same year. This has been the case in the Netherlands for a hundred years,’ says sign linguist Richard Cokart, who works at the Dutch Sign Language Centre (NGC). This has created gaps in the sign language lexicon, which has had far-reaching negative consequences for the educational, social, emotional and cultural development of deaf people. This is also the case in countries such as Belgium, Germany, Great Britain and (with a few exceptions) the United States.

Deaf people therefore usually ended up in practical occupations such as shoemaking or tailoring. ‘They had no opportunity to study or work at a scientific level’, Cokart continues. Nowadays there are many more facilities, including sign language interpreters, so deaf people have more access to information. That’s why I could become a linguist, for example, and others could become lawyers, dentists and so on. And so the road to STEM [Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics, ed.] has also slowly been paved.’ A big step forward is the recognition of Dutch Sign Language (NGT) as an official language in the Netherlands in 2020. Flemish Sign Language (VGT) was already recognised in 2006.

How to develop signs

One of the consequences of the long absence of sign language in education is that many concepts still have no sign, especially in STEM. ‘Many students work with an interpreter and then make up temporary signs’, says Cokart. ‘But because it is not standardised, you have to start from scratch in new environments or with new people.’

Audrey Cameron, Chancellor’s Fellow at the University of Edinburgh and Chair of the British Sign Language (BSL) Working Group, agrees. ‘As a deaf chemist, I have encountered many barriers’, says the polymer chemist. ‘The biggest challenge was that there were no sign language interpreters who knew much about chemistry, so it was difficult to communicate with colleagues. This is why I have shifted my focus to education, in the hope of providing a better experience for other deaf scientists.’

So the British Sign Language STEM Glossary project was born, involving sign language researchers, deaf teachers and (PhD) deaf scientists, as well as Cameron. The aim of the project was to add a large number of STEM signs to the BSL lexicon. ‘It is important to involve deaf people in this because it is their own natural language’, explains Cameron. ‘For example, a scientist will come up with a sign for a particular concept. A linguist looks at the BSL rules and can point out things that don’t quite work. A teacher then looks at it again from an educational point of view: how does the sign visualise the concept, is the meaning clear to the students?’ The project’s website now contains many gestures for chemistry, biology, maths and physics, among other subjects.

Sign workshop

A similar approach is used in the Netherlands. ‘A number of interpreters asked us to develop more signs and add them to our online dictionary’, Cokart explains. ‘To this end, we set up “sign workshops” [gebarenateliers, ed.], groups of people who work in a particular field and therefore come into contact with signs on a regular basis.’ Recently, a sign workshop was set up for molecular biology. ‘As a sign language centre, we have little knowledge of this ourselves, but an interpreter and a deaf student working together provided us with a whole list, including videos of self-made signs to go with the terms.’

Despite the fact that the deaf community is relatively small (20,000 in the Netherlands, 12,000 of whom use NGT), a total of eight people managed to arrange a meeting. Cokart: ‘During this meeting we watched the videos made by the deaf person and the interpreter mentioned above, evaluated the signs they suggested, made linguistic adjustments where necessary and then added them to the online sign dictionary.’

This is not always easy. ‘Deaf people think very visually and are very critical about how a sign is performed, but they are also used to their own self-made signs’, says Cokart. For example, we talked a lot about the axon, which is the long, slender projection of a nerve cell. If you make an open hand, you have the gesture for a nerve cell. Then, using the thumb and forefinger of the other hand, you make a movement upwards from the thumb, representing the projection. ‘When inventing signs, you have to stick to the so-called semantic line: so the basic sign for a nerve cell is this open hand. Anything that then has to do with nerve cells must stick to this basic gesture, so that the coherence is maintained.’

Gap projects

There are also projects of this kind in Flanders, the so-called gap projects [hiatenprojecten, ed.]. ‘These focus on identifying and documenting missing signs’, says Hannes De Durpel, coordinator at the Flemish Sign Language Centre (VGTC), by email. ‘For each gap project, a new group of participants with expertise in the specific area whose lexicon is being researched is assembled. During the meetings, the signs already accumulated are discussed and new signs are collected. Then there is a survey of whether all these signs have been seen and/or used by the participants. Depending on the answers, a gesture is approved, passed on to another verification channel, or rejected. The fact that a sign can go through several verification channels before it is approved means that it can take some time before the use status of a sign in Flanders is finally clear. This careful process ensures the quality and reliability of the lexicon.’

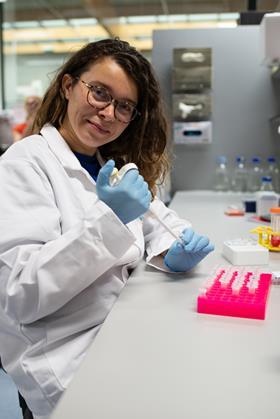

Amelie Fossoul, a deaf laboratory scientist in Flanders, is herself very involved with scientific signs. ‘I contacted the Flemish Sign Language Centre several times in the past about the scientific lexicon, but I was always told that they were too busy or working on another project.’ However, the VGTC regularly asks her for specific signs needed for interpreting the news.

‘I would very much like to start a new project within the VGTC to expand the vocabulary of signs’, says Fossoul. ‘Last year the VGTC convened a group of deaf scientists and nurses to discuss this. Unfortunately, it stopped there, and that is not enough to really take meaningful steps.’

Spreading the signs is important to Fossoul, but she also prefers to have them officially registered. ‘You see that people sometimes misuse signs and I regularly help other deaf people with words like DNA, RNA, genes and proteins. An example of possible confusion occurred during the COVID pandemic. At press conferences they were signing “corona” very similar to the sign for “destruction”. We were able to point this out to them and then, fortunately, adjustments were made.’

According to Fossoul, more research into the scientific lexicon of signs, led by scientists, is urgently needed. You need deaf people or interpreters with the right knowledge and experience for this kind of project’, says Fossoul. ‘More and more deaf students are entering mainstream education these days, and they would benefit if the VGTC were to carry out comprehensive research into scientific jargon and sign language. Many scientific terms used in secondary education should have been included in the VGTC sign language dictionary long ago, so that they could have been passed on to the next generations.’

Barriers for deaf people

The experiences of deaf people in science vary, depending on the institute where they work or study. ‘At the Rochester Institute of Technology, I received a lot of support from the National Technical Institute for the Deaf when I was studying biochemistry’, says Annemarie Ross, associate professor at RIT/NTID. ‘Think note takers, interpreters and live captioning during class. It was only after college that things started to get tricky.’

Now it was not all plain sailing. ‘Especially with people who had no experience of working with deaf people, I often had to explain how to do it’, says Ross. Cameron confirms that there is still progress to be made. ‘There are more campaigns now and we get regular funding to develop new signs, but it is never enough to maintain a stable team over a long period of time. That is why we are so grateful for the support of the Royal Society of Chemistry, which are very supportive of this kind of project.’

In practical terms, universities and other institutions can do a lot to help deaf people, even with small adjustments. ‘For example: PowerPoint has an option to generate live captioning that you can turn on during lectures’, says Cameron. ‘Simple, but much more accessible for deaf people.’ Ross adds: ‘Often employers find security a big barrier to allowing deaf people to work in the lab. But there are ways of doing this, such as flashes of light in addition to an audible signal in the event of an emergency.’

Communication in the lab

So what is the best way to communicate with a deaf person in the lab? ‘If colleagues are open to it, it’s not difficult’, says Ross. ‘Of course, if you can, it helps to learn some signs that you use a lot in the lab, such as a beaker or a particular instrument.’ She can use her voice to make herself understood and lip-read if colleagues don’t know American Sign Language.

Fossoul provides an interpreter with the right scientific knowledge when she has meetings. ‘But there is a serious shortage of interpreters. Also, many interpreters are reluctant to interpret in a field as specific as life sciences.’ In face-to-face communication, both people have to put in a bit more effort and work a bit more visually. ‘I can make myself understood quite well to my Flemish colleagues, and when I feel good and energetic, it is also a bit easier to lip-read and understand what someone means.’ It also helps if someone uses a bit more body language. ‘I once had an Italian colleague who was learning Dutch. She dared to speak Dutch with me, but she found it more exciting with my hearing colleagues. I could follow her very well because, as a southern European, she spoke much more animatedly than most northern Europeans.’

Benefits of sign language

But sign language also has advantages for hearing people. ‘Many laboratories have large windows between closed rooms’, says Cokart. ‘So if you can’t understand each other, you can communicate through the glass.’ In addition, research shows that hearing people who learn signs get a better working memory and therefore learn better, he explains. ‘It can also help with remembering concepts. You see that with the sign for axon, you remember it much faster because of that visual link.’

‘Chemistry is very abstract’, adds Cameron. ‘There are often no definitive visualisations. On the one hand, that makes it difficult to design signs, but on the other hand, it’s a great way to visualise these kinds of abstract concepts, even for hearing people.’ And Fossoul adds: ‘And because sign language is so visual, it is very suitable for explaining science.’

‘Finally, it is good to realise that there are amazing people who are deaf or have other disabilities who are talented and who go on to get PhDs’, says Ross. ‘It would be a shame to miss out on these people just because of their disability.’

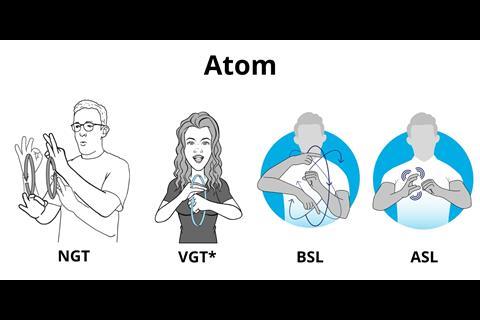

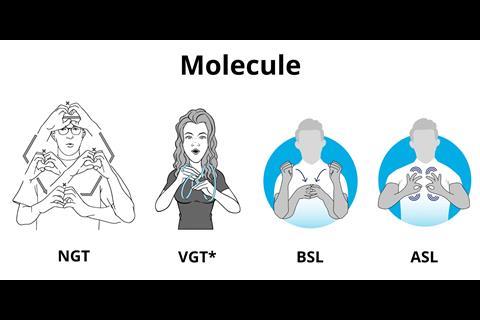

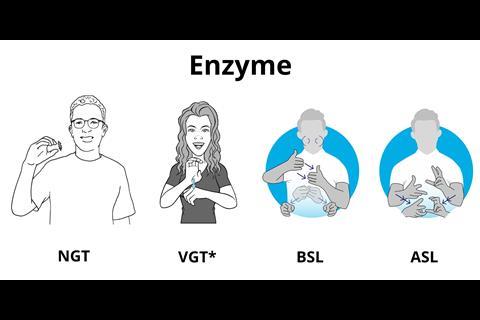

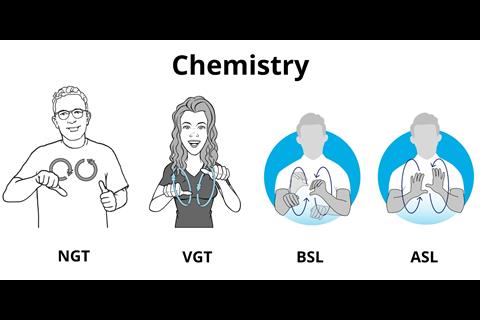

Designs: NGT: Bart Koolen, NGC; VGT*: Filip Heyninck; BSL/ASL: The Videomatic, checked by Audrey Cameron en Annemarie Ross. *The VGT signs for ‘atom’, ‘molecule’ and ‘enzyme’ are not officially verified by the VGTC.

Examples of signs

We asked Cameron, Cokart, Fossoul and Ross for signs that they find interesting or visually strong. Note that these signs are all in different languages and are not interchangeable. In addition, the signs in VGT are not yet officially recognised by the VGTC.

Richard Cokart (NGT):

Fluorescence: Hold your left arm out in front of your body with the palm facing up. Your right hand starts diagonally above. Make an open hand (sign for light) and then move that hand as a fist to your left hand. From there you continue upwards with an open hand. This symbolises the energy of incoming light hitting a material and resulting in outgoing light.

Gravitopism: Plants always grow towards the light. If you turn them around, they still grow towards the light, but in a curve. So this is what the sign looks like: you hold one fist horizontally in front of you, and with your other hand you start with a finger on your fist and make a quarter circle upwards. The moment you sign it, it is immediately clear, even to people who have never heard of the term.

Hydrophilic/hydrophobic: this follows a semantic line. Everything with -philic you represent as wiggling fingers with the palms facing you, and with -phobic you also do wiggling fingers but with the palms facing outwards and away from you. So you combine the sign for water with -philic or -phobic.

Audrey Cameron (BSL):

Atom: Make a fist with one hand and extend only your index finger sideways. Your index finger symbolises the negatively charged electron. Then circle around your fist like an electron in an orbital. Depending on how you move your finger, you can show different orbitals.

Redox reaction: Make two fists in front of your body to symbolise two atomic nuclei. Then make the sign for an atom by moving the ‘electron’ (your index finger) from one fist (atom) to where your other fist (atom) was. This shows how an electron is transferred in a redox reaction. If you do this faster or slower, you can also show how fast the reaction is going, or even sign an energy diagram with a reaction barrier.

Annemarie Ross (ASL):

‘I once joined a group to develop sustainability signs and one of my favourites is environmental sustainability.’

Environmental Sustainability: This sign has three steps. 1) Raise your index finger and hover over it with your flat hand. 2) Make a hook with both index fingers and switch hands. 3) Then make a fist with your thumbs together and move the whole forward. The whole represents preserving or maintaining the environment with an emphasis on renewable resources.

Electron: This is a sign you can build on (similar to the atom in BSL). Hold your index finger horizontally and make circles with your finger only. To sign a specific orbital, move your finger in the shape of the orbital.

Amelie Fossoul (VGT, not yet verified):

DNA/RNA: For DNA, use both hands to make a V-shape with your index and middle fingers, holding your fingertips together and horizontally in front of your body. Now make a twisting movement to the side as your hands separate. This is how you sign the DNA helix. Do the same for RNA, but with one finger on each hand, as RNA is similar to single-stranded DNA.

Dendritic cells: hold up the index, middle and ring fingers of both hands with your palms facing you; wiggle your fingers alternately.

Macrophages: make some grasping movements in front of your body, palms down.

Thanks to the sign language interpreters:

Siegrid Leurs (VGT)

Luca Konrad (NGT)

Abigail Sheridan (BSL)

Z-video relay service (ASL)

Nog geen opmerkingen